European Economic Area

European Economic Area

| |

|---|---|

EU states which form part of the EEA

EFTA states which form part of the EEA | |

|

|

| Member states[1][2] | All 27 EU member states 3 of 4 EFTA member states |

| Establishment | |

• EEA Agreement signed | 2 May 1992 |

• Entry into force | 1 January 1994 |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,945,000 km2 (1,909,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | 453,000,000 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | US$16.3 trillion[3] |

• Per capita | US$39,500 |

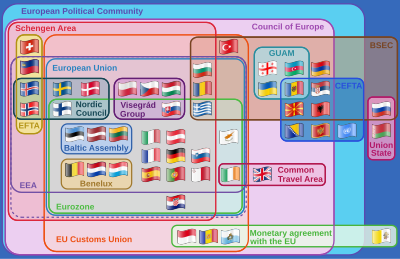

The European Economic Area (EEA) was established via the Agreement on the European Economic Area,[4] an international agreement which enables the extension of the European Union's single market to member states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA).[5] The EEA links the EU member states and three of the four EFTA states (Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway) into an internal market governed by the same basic rules. These rules aim to enable free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital within the European single market, including the freedom to choose residence in any country within this area. The EEA was established on 1 January 1994 upon entry into force of the EEA Agreement. The contracting parties are the EU, its member states, and Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway.[4] New members of EFTA would not automatically become party to the EEA Agreement, as each EFTA State decides on its own whether it applies to be party to the EEA Agreement or not. According to Article 128 of the EEA Agreement, "any European State becoming a member of the Community shall, and the Swiss Confederation or any European State becoming a member of EFTA may, apply to become a party to this Agreement. It shall address its application to the EEA Council." EFTA does not envisage political integration. It does not issue legislation, nor does it establish a customs union. Schengen is not a part of the EEA Agreement. However, all of the four EFTA States participate in Schengen and Dublin through bilateral agreements. They all apply the provisions of the relevant Acquis.[6]

The EEA Agreement is a commercial treaty and differs from the EU Treaties in certain key respects. According to Article 1 its purpose is to "promote a continuous and balanced strengthening of trade and economic relation". The EFTA members do not participate in the Common Agricultural Policy or the Common Fisheries Policy.

The right to free movement of persons between EEA member states and the relevant provisions on safeguard measures are identical to those applying between members of the EU.[4][7] The right and rules applicable in all EEA member states, including those which are not members of the EU, are specified in Directive 2004/38/EC[7] and in the EEA Agreement.[4][8]

The EEA Agreement specifies that membership is open to member states either of the EU or of the EFTA. EFTA states that are party to the EEA Agreement participate in the EU's internal market without being members of the EU or the European Union Customs Union. They adopt most EU legislation concerning the single market, with notable exclusions including laws regarding the Common Agricultural Policy and Common Fisheries Policy.[9] The EEA's "decision-shaping" processes enable EEA EFTA member states to influence and contribute to new EEA policy and legislation from an early stage.[10] Third country goods are excluded for these states on rules of origin.

When entering into force in 1994, the EEA parties were 17 states and two European Communities: the European Community, which was later absorbed into the EU's wider framework,[citation needed] and the now defunct European Coal and Steel Community. Membership has grown to 30 states as of 2020: 27 EU member states, as well as three of the four member states of the EFTA (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway).[4] The Agreement is applied provisionally with respect to Croatia—the remaining and most recent EU member state—pending ratification of its accession by all EEA parties.[2][11] One EFTA member, Switzerland, has not joined the EEA, but has a set of bilateral sectoral agreements with the EU which allow it to participate in the internal market.

Origins

[edit]In the late 1980s, the EFTA member states, led by Sweden, began looking at options to join the then-existing European Economic Community (EEC), the precursor of the European Union (EU). The reasons identified for this are manifold. Many authors cite the economic downturn at the beginning of the 1980s, and the subsequent adoption by the EEC of the "Europe 1992 agenda", as a primary reason. Arguing from a liberal intergovernmentalist perspective, these authors argue that large multinational corporations in EFTA countries, especially Sweden, pressed for EEC membership under threat of relocating their production abroad. Other authors point to the end of the Cold War, which made joining the EEC less politically controversial for neutral countries.[12]

Meanwhile, Jacques Delors, who was President of the European Commission at the time, did not like the idea of the EEC enlarging with more member states, as he feared that it would impede the ability of the Community to complete internal market reform and establish monetary union. He proposed a European Economic Space (EES) in January 1989, which was later renamed the European Economic Area, as it is known today.[12]

By the time the EEA was established in 1994, however, several developments hampered its credibility. First of all, Switzerland rejected the EEA agreement in a national referendum on 6 December 1992, obstructing full EU-EFTA integration within the EEA. Furthermore, Austria had applied for full EEC membership in 1989, and was followed by Finland, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland between 1991 and 1992 (Norway's EU accession was rejected in a referendum, Switzerland froze its EU application after the EEA agreement was rejected in a referendum). The fall of the Iron Curtain had made the EU less hesitant to accept these highly developed countries as member states, since that would relieve the pressure on the EU's budget when the former socialist countries of Central Europe were to join.[12]

Membership

[edit]

The EEA Agreement was signed in Porto on 2 May 1992 by the then seven states of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), the European Community (EC) and its then 12 member states.[13][14] On 6 December 1992, Switzerland's voters rejected the ratification of the agreement in a constitutionally mandated referendum,[15] effectively freezing the application for EC membership submitted earlier in the year. Switzerland is instead linked to the EU by a series of bilateral agreements. On 1 January 1995, three erstwhile members of the EFTA—Austria, Finland and Sweden—acceded to the European Union, which had superseded the European Community upon the entry into force of the Maastricht Treaty on 1 November 1993. Liechtenstein's participation in the EEA was delayed until 1 May 1995.[16] Any European State becoming a member of the EU shall, or becoming a member of EFTA may, apply to become a Party to the EEA agreement according to article 128 of the agreement.[4]

As of 2020[update], the contracting parties to the EEA are three of the four EFTA member states and the 27 EU member states.[17] The newest EU member, Croatia, finished negotiating their accession to the EEA in November 2013,[18] and since 12 April 2014 has provisionally applied the agreement pending its ratification by all EEA member states.[2][11]

Treaties

[edit]Besides the 1992 Treaty, one amending treaty was signed, as well as three treaties to allow for accession of new members of the European Union.

| Treaty | Signature | Entry into force | Original signatories | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EEA agreement | 2 May 1992 | 1 January 1994 | 19 states + EEC and ECSC | Entered into force as adjusted by the 1993 Protocol |

| Adjusting Protocol | 17 March 1993 | 1 January 1994 | 18 states + EEC and ECSC | Allowing entry into force without Switzerland |

| Participation of 10 new States | 14 October 2003 | 6 December 2005 | 28 states + EC | In view of 2004 enlargement of the European Union |

| Participation of two new States | 25 July 2007 | 9 November 2011 | 30 states + EC | Following 2007 enlargement of the European Union |

| Participation of one new State | 11 April 2014 | not yet in force | 31 states + EU | Following 2013 enlargement of the European Union |

Ratification of the EEA Agreement

[edit]| State | Signed [Note 1][1][19] |

Ratified [Note 1][1] |

Entered into force[1] | Exit | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 May 1992 | 15 October 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EU member (from 1 January 1995) Acceded to the EEA as an EFTA member[19] | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 9 November 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 25 July 2007 | 29 February 2008 | 9 November 2011 | EU member | ||

| 11 April 2014 | 24 March 2015[21] | No[22] | EU member (from 1 July 2013) Provisional application (as a participating non-EEA state) from 12 April 2014[2] | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 30 April 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member (The application (and implementation) of the agreement is suspended in territories known as Northern Cyprus[Note 2]) | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 10 June 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 30 December 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 13 December 1993 | 1 January 1994 | Originally as European Economic Community and European Coal and Steel Community | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 13 May 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 17 December 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EU member (from 1 January 1995) Acceded to the EEA as an EFTA member[19] | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 10 December 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 23 June 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 10 September 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 26 April 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 4 February 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EFTA member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 29 July 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 15 November 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 4 May 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 25 April 1995 | 1 May 1995 | EFTA member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 27 April 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 21 October 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 5 March 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 31 December 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 19 November 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EFTA member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 8 October 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 9 March 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 25 July 2007 | 23 May 2008 | 9 November 2011 | EU member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 19 March 2004 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 14 October 2003 | 30 June 2005 | 6 December 2005 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 3 December 1993 | 1 January 1994 | EU member | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 18 December 1992 | 1 January 1994 | EU member (from 1 January 1995) Acceded to the EEA as an EFTA member[19] | ||

| 2 May 1992 | No | No | EFTA member EEA ratification rejected in a 1992 referendum Removed as contracting party in 1993 protocol | ||

| 2 May 1992 | 15 November 1993 | 1 January 1994 | 31 January 2020 | Former EEA and EU member. EEA covered (with exceptions) Gibraltar and the Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia as well as including (for limited purposes) the three Crown Dependencies (Isle of Man, Jersey and Guernsey). The EEA Agreement and EEA Regulations remained applicable in respect of the UK (and the UK in respect of the aforementioned Associated Territories) during the Transition period (also known in the UK as the Implementation period) until 31 December 2020.[28] |

Notes

- ^ a b Of the original agreement, or a subsequent agreement on participation of that particular state in the EEA.

- ^ Protocol 10 of the treaty of accession of the European Union to Cyprus suspended the application of the EU acquis to Northern Cyprus.[24][25] The EEA Agreement states that it only applies to the territories of EU member states to which the EU treaties apply.[26] A joint declaration to the Final Act of treaty on accession of Cyprus to the EEA confirmed that this included the Protocol on Cyprus.[27]

Future enlargement

[edit]Recent EU member states

[edit]When a state joins the EU, they do not necessarily immediately become part of the EEA but are obliged to apply.[29] Following the 2004 enlargement of the EU, which saw Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia acceding to the EU on 1 May 2004, the EEA Enlargement Agreement was applied on a provisional basis to the 10 acceding countries as from the date of their accession in May 2004 to the EU.[30] On the other hand, following the 2007 enlargement of the EU, which saw Bulgaria and Romania acceding to the EU on 1 January 2007, an EEA Enlargement Agreement was not signed until 25 July 2007 and only provisionally entered into force on 1 August 2007.[31][32][20] The agreement did not fully enter into force until 9 November 2011.[20]

- Croatia

Prior to the 2013 enlargement of the EU, which saw Croatia acceding to the EU on 1 July 2013, an EEA Enlargement Agreement was not signed. Croatia signed its Treaty of Accession to the EU on 9 December 2011[33] and subsequently lodged their application to the EEA on 13 September 2012.[34] Negotiations started on 15 March 2013 in Brussels, with the aim of achieving simultaneous accession to both the EU and the EEA on 1 July 2013.[35] However, this was not achieved.[36][37][38][39]

On 20 November 2013, it was announced that an enlargement agreement was reached. The text was initialled on 20 December 2013, and following its signature in April 2014 the agreement is being provisionally applied pending ratification by Croatia, all EEA states, and the European Union.[11][18][40] As of January 2025, the agreement has been ratified by 30 out of 31 parties, all except the European Union.[2]

Future EU member states

[edit]There are nine recognised candidates for membership of the European Union: Turkey (since 1999), North Macedonia (2005), Montenegro (2010), Serbia (2012), Albania (2014), Moldova (2022), Ukraine (2022), Bosnia and Herzegovina (2022) and Georgia (2023). Kosovo (whose independence is not recognised by five EU member states) formally submitted its application for membership in 2022 and is considered a potential candidate by the European Union.[41][42]

Faroe Islands

[edit]In mid-2005, representatives of the Faroe Islands hinted at the possibility of their territory joining the EFTA.[43] However, the ability of the Faroes to join is uncertain because, according to Article 56 of the EFTA Convention, only states may become members of the Association.[44] The Faroes, which form part of the Danish Realm, is not a sovereign state, and according to a report prepared for the Faroes Ministry of Foreign Affairs "under its constitutional status the Faroes cannot become an independent Contracting Party to the EEA Agreement due to the fact that the Faroes are not a state".[45] However, the report went on to suggest that it is possible that the "Kingdom of Denmark in respect of the Faroes" could join the EFTA.[45] The Danish Government has stated that the Faroes cannot become an independent member of the EEA as Denmark is already a party to the EEA Agreement.[45] The Faroes already have an extensive bilateral free trade agreement with Iceland, known as the Hoyvík Agreement.

Switzerland

[edit]A referendum of 1992 rejected this, and there is a prevalent opinion among EU/EEA countries that Swiss referendums would disrupt the EEA-EU cooperation, like has happened with the Switzerland-EU cooperation.[46]

A poll in December 2022 to mark 30 years since the 1992 EEA referendum indicated that 71% would vote for EEA participation if a referendum were held.[47] For common Swiss people, a major difference between EEA and the Swiss agreement, is that EEA includes free movement for services including roaming prices for mobile phones. A members bill about joining EEA in 2022 was mostly rejected by the Federal council (government) considering the present treaties better for Switzerland.[48]

European microstates

[edit]In November 2012, after the Council of the European Union had called for an evaluation of the EU's relations with the sovereign European microstates of Andorra, Monaco and San Marino, which they described as "fragmented",[49] the European Commission published a report outlining options for their further integration into the EU.[50] Unlike Liechtenstein, which is a member of the EEA via the EFTA and the Schengen Agreement, relations with these three states are based on a collection of agreements covering specific issues. The report examined four alternatives to the current situation: 1) a Sectoral Approach with separate agreements with each state covering an entire policy area, 2) a comprehensive, multilateral Framework Association Agreement (FAA) with the three states, 3) EEA membership, and 4) EU membership. The Commission argued that the sectoral approach did not address the major issues and was still needlessly complicated, while EU membership was dismissed in the near future because "the EU institutions are currently not adapted to the accession of such small-sized countries". The remaining options, EEA membership and an FAA with the states, were found to be viable and were recommended by the commission.

As EEA membership is currently only open to EFTA or EU members, the consent of existing EFTA member states is required for the microstates to join the EEA without becoming members of the EU. In 2011, Jonas Gahr Støre, the then Foreign Minister of Norway, which is an EFTA member state, said that EFTA/EEA membership for the microstates was not the appropriate mechanism for their integration into the internal market because their requirements differed from those of larger countries such as Norway, and suggested that a simplified association would be better suited for them.[51] Espen Barth Eide, Støre's successor, responded to the commission's report in late 2012 by questioning whether the microstates have sufficient administrative capabilities to meet the obligations of EEA membership. However, he stated that Norway was open to the possibility of EFTA membership for the microstates if they decide to submit an application, and that the country had not made a final decision on the matter.[52][53][54][55] Pascal Schafhauser, the Counsellor of the Liechtenstein Mission to the EU, said that Liechtenstein, another EFTA member state, was willing to discuss EEA membership for the microstates provided their joining did not impede the functioning of the organisation. However, he suggested that the option of direct membership in the EEA for the microstates, outside both the EFTA and the EU, should be given consideration.[54]

On 18 November 2013, the EU Commission concluded that "the participation of the small-sized countries in the EEA is not judged to be a viable option at present due to the political and institutional reasons", and that Association Agreements were a more feasible mechanism to integrate the microstates into the internal market.[56]

Withdrawal of the United Kingdom

[edit]The United Kingdom, in a 2016 referendum, voted to withdraw from the European Union. Staying in the EEA, possibly eventually as an EFTA member, was an option suggested by the then Environment Secretary, Michael Gove.[57]

A 2013 research paper presented to the Parliament of the United Kingdom proposed a number of alternatives to EU membership which would continue to allow it access to the EU's internal market, including continued EEA membership as an EFTA member state, or the Swiss model of a number of bilateral treaties covering the provisions of the single market.[58] The United Kingdom was a co-founder of EFTA in 1960, but ceased to be a member upon joining the European Community. In the first meeting since the Brexit vote, EFTA reacted by saying both that it was open to a United Kingdom return and that it had many issues to work through[59] although the Norwegian Government later expressed reservations.[60] In January 2017, Theresa May, then the British prime minister, announced a 12-point plan of negotiating objectives and confirmed that the government of the United Kingdom would not seek continued permanent membership in the single market.[61] The United Kingdom could be allowed by other member states to join the EEA and EFTA but existing EEA members such as Norway would have concerns about taking the risk of opening a difficult negotiation with the EU that could lead them to lose their current advantages.[62] The Scottish Government has looked into membership of the EFTA to retain access to the EEA.[63] However, other EFTA states have stated that only sovereign states are eligible for membership, so it could only join if it became independent from the United Kingdom.[64]

The EEA EFTA States (Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein) signed a Separation Agreement with the UK on 28 January 2020, which is understood to mirror the EEA-relevant parts of the EU-UK Withdrawal Agreement.[28] The withdrawal agreement stipulated a transition period, following the UK's formal withdrawal on 31 January 2020 and ending 31 December 2020, during which both the United Kingdom and the other EEA members remained bound by the existing obligations stemming from international agreements concluded by the EU, including the EEA Agreement.[28] In January and February 2020, the government of the United Kingdom ruled out a future alignment to the rules of the internal market, effectively ruling out EEA membership after the end of the transition period on 31 December 2020.[65][66][67]

Rights and obligations

[edit]The EEA relies on the same "four freedoms" underpinning the European single market as does the European Union: the free movement of goods, persons, services, and capital among the EEA countries. Thus, the EEA countries that are not part of the EU enjoy free trade with the European Union. Also, the 'free movement of persons is one of the core rights guaranteed in the European Economic Area (EEA) [...]. It is perhaps the most important right for individuals, as it gives citizens of the 30 EEA countries the opportunity to live, work, establish business and study in any of these countries'.[68]

As a counterpart, these countries have to adopt part of the Law of the European Union. However they also contribute to and influence the formation of new EEA relevant policies and legislation at an early stage as part of a formal decision-shaping process.[10]

Agriculture and fisheries are not covered by the EEA. Not being bound by the Common Fisheries Policy is perceived as very important by Norway and Iceland, and a major reason not to join the EU. The Common Fisheries Policy would mean giving away fishing quotas in their waters.

The EEA countries that are not part of the EU do not contribute financially to Union objectives to the same extent as do its members, although they contribute to the EEA Grants scheme to "reduce social and economic disparities in the EEA". Additionally, some choose to take part in EU programmes such as Trans-European Networks and the European Regional Development Fund. Norway also has its own Norway Grants scheme.[69] After the EU/EEA enlargement of 2004, there was a tenfold increase in the financial contribution of the EEA States, in particular Norway, to social and economic cohesion in the Internal Market (€1167 million over five years).[citation needed]

Legislation

[edit]

The non-EU members of the EEA (Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway) have agreed to enact legislation similar to that passed in the EU in the areas of social policy, consumer protection, environment, company law and statistics.[citation needed] These are some of the areas covered by the former European Community (the "first pillar" of the European Union).

The non-EU members of the EEA are not represented in Institutions of the European Union such as the European Parliament or European Commission. This situation has been described as "fax democracy", with Norway waiting for their latest legislation to be faxed from the commission.[70][71] However, EEA countries are consulted about new EU legislative proposals and participate in shaping legislation at an early stage. The EEA Agreement contains provisions for input from the EEA/EFTA countries at various stages before legislation is adopted, including consent at the EEA Joint Committee. Once approved at the EEA Joint Committee, it is part of the EEA Agreement, and the EFTA states within the EEA must implement it in their national law.[72]

Institutions

[edit]The EEA Joint Committee consists of the EEA-EFTA States plus the European Commission (representing the EU) and has the function of amending the EEA Agreement to include relevant EU legislation. An EEA Council meets twice yearly to govern the overall relationship between the EEA members.

Rather than setting up pan-EEA institutions, the activities of the EEA are regulated by the European Union institutions, as well as the EFTA Surveillance Authority and the EFTA Court. The EFTA Surveillance Authority and the EFTA Court regulate the activities of the EFTA members in respect of their obligations in the European Economic Area (EEA). The EFTA Surveillance Authority performs the European Commission's role as "guardian of the treaties" for the EFTA countries to ensure the EEA Agreement is being followed. The EFTA Court performs a similar role to the European Court of Justice's in that it resolves disputes under the EEA Agreement.

While the ECJ and European Commission are respectively responsible for the interpretation and application of the EEA Agreement in the EU (between EU member states and within EU member states), and the EFTA Court and EFTA Surveillance Authority are likewise respectively responsible for interpreting and monitoring the application of the EEA Agreement among the EEA-EFTA states (between the EEA-EFTA states and within the EEA-EFTA states), disputes between an EU state and an EEA-EFTA state are referred to the EEA Joint Committee rather to either court. Only if the Joint Committee cannot provide a resolution within three months, would the disputing parties jointly submit to the ECJ for a ruling (if the dispute concerns provisions identical to EU law) or to arbitration (in all other cases).[73]

The original plan for the EEA lacked the EFTA Court or the EFTA Surveillance Authority, as the "EEA court" (which would be composed of five European Court of Justice members and three members from EFTA countries and which would be functionally integrated with the ECJ)[74] and the European Commission were to exercise those roles. However, during the negotiations for the EEA agreement, the European Court of Justice informed the Council of the European Union (Opinion 1/91) that they considered that giving the EEA court jurisdiction with respect to EU law that would be part of the EEA law, would be a violation of the treaties, and therefore the current arrangement was developed instead. After having negotiated the Surveillance Authority, the ECJ confirmed its legality in Opinion 1/92.

The EFTA Secretariat is headquartered in Geneva, Switzerland. The EFTA Surveillance Authority has its headquarters in Brussels, Belgium (the same location as the headquarters of the European Commission), while the EFTA Court has its headquarters in Luxembourg (the same location as the headquarters of the European Court of Justice).

EEA and Norway Grants

[edit]The EEA and Norway Grants are the financial contributions of Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway to reduce social and economic disparities in Europe. In the period from 2004 to 2009, €1.3 billion of project funding is made available for project funding in the 15 beneficiary states in Central and Southern Europe.

Established in conjunction with the 2004 enlargement of the European Economic Area (EEA), which brings together the EU, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway in the Internal Market, the EEA and Norway Grants were administered by the Financial Mechanism Office, which is affiliated to the EFTA Secretariat in Brussels.

See also

[edit]- EudraVigilance

- Eurasian Economic Union

- European integration

- European Union Customs Union

- Free trade area

- Free trade areas in Europe

- Iceland–European Union relations

- Liechtenstein–European Union relations

- Market access

- Norway–European Union relations

- Parallel import

- Potential enlargement of the European Union

- Rules of origin

- Schengen Agreement

- Societas cooperativa Europaea

- Switzerland–European Union relations

- Tariff

- Trade bloc

- Vehicle insurance in France

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d "Agreement details". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 20 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f "Agreement details". Council of the European Union. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". imf.org. Archived from the original on 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Agreement on the European Economic Area (Consolidated text)

- ^ "The Basic Features of the EEA Agreement - European Free Trade Association". efta.int. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ "Frequently asked questions on EFTA, the EEA, EFTA membership and Brexit | European Free Trade Association".

- ^ a b Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States amending Regulation (EEC) No 1612/68 and repealing Directives 64/221/EEC, 68/360/EEC, 72/194/EEC, 73/148/EEC, 75/34/EEC, 75/35/EEC, 90/364/EEC, 90/365/EEC and 93/96/EEC

- ^ Decision of the EEA Joint Committee No 158/2007 of 7 December 2007 amending Annex V (Free movement of workers) and Annex VIII (Right of establishment) to the EEA Agreement

- ^ "The Basic Features of the EEA Agreement | European Free Trade Association". Efta.int. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b "2182-BULLETIN-2009-07:1897-THIS-IS-EFTA-24" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 August 2011. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ a b c "Croatia joins the EEA". European Free Trade Association. 12 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Bache, Ian and Stephen George (2006) Politics in the European Union. Second Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 543–548.

- ^ "1992". The EU at a glance – The History of the European Union. Europa. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ "Final Act". Archived from the original on 16 May 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2010. (434 KB)

- ^ Mitchener, Brandon (7 December 1992). "EEA Rejection Likely to Hurt Swiss Markets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ "1995". The EU at a glance – The History of the European Union. Europa. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ^ Information relating to the provisional application of an Agreement on the participation of the Republic of Croatia in the European Economic Area

- ^ a b "Croatia joins the EEA". Government of Norway. 20 November 2013. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Agreement on the European Economic Area". European Union. 8 January 2010. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Agreement details". Council of the European Union. 25 July 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Hrvatski sabor". Sabor.hr. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "Agreement on the participation of the Republic of Croatia in the European Economic Area". The Council of the EU. Retrieved 21 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Agreement details". Council of the European Union. 14 October 2003. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ Act concerning the conditions of accession of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Estonia, the Republic of Cyprus, the Republic of Latvia, the Republic of Lithuania, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Malta, the Republic of Poland, the Republic of Slovenia and the Slovak Republic and the adjustments to the Treaties on which the European Union is founded - Protocol No 10 on Cyprus

- ^ "Turkish Cypriot Community". European Commission. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "AGREEMENT ON THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AREA" (PDF). European Free Trade Association. p. 40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ "AGREEMENT on the participation of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Estonia, the Republic of Cyprus, the Republic of Latvia, the Republic of Lithuania, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Malta, the Republic of Poland, the Republic of Slovenia and the Slovak Republic in the European Economic Area". European Union. 29 April 2004. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 30 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Frequently asked questions on EFTA, the EEA, EFTA membership and Brexit". EFTA. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ^ "EEA Agreement" (PDF). European Free Trade Association. Article 128. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ 2004/368/EC: Council Decision of 30 March 2004 concerning the provisional application of the Agreement on the participation of the Czech Republic, the Republic of Estonia, the Republic of Cyprus, the Republic of Hungary, the Republic of Latvia, the Republic of Lithuania, the Republic of Malta, the Republic of Poland, the Republic of Slovenia and the Slovak Republic in the European Economic Area and the provisional application of four related agreements

- ^ "Enlargement of the EU and the EEA". Mission of Norway to the EU. 8 June 2009. Archived from the original on 5 August 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Enlargement of the EEA". European Free Trade Association. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ^ "Croatians vote "Yes" to EU accession". 22 January 2012. Archived from the original on 23 January 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "Croatian gov't files for Croatia's entry into EEA". 13 September 2012. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ Europaportalen (15 March 2013). "Forhandlinger med Kroatia om medlemskap i EØS" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 6 September 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- ^ "Conclusions of the 40th meeting of the EEA Council Brussels, 19 November 2013" (PDF). Council of the EEA. 19 November 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ "Minister of Foreign Affairs: European Economic Area should work on reducing economic disparities". Council of the European Union. 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 3 November 2018. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ "Kroatia inn i EU" (in Norwegian). Norwegian Directorate of Immigration. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 19 February 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Norway congratulates Croatia on EU membership". The Royal Norwegian Embassy in Zagreb. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- ^ "Croatia one step closer to the EEA". European Free Trade Association. 20 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- ^ "Candidate Countries - Enlargement - Environment - European Commission". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "Joining the EU". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 29 December 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- ^ Spongenberg, Helena (8 October 2007). "Faroe Islands seek closer EU relations". EUobserver. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "Convention Establishing the European Free Trade Association" (PDF). 21 June 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ a b c "The Faroes and the EU – possibilities and challenges in a future relationship" (PDF). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Faroes. 2010. p. 53. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Bondolfi, Sibilla (7 December 2022). "Switzerland and EEA membership: not as simple as it sounds". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Skepsis gegenüber der EU auch 30 Jahre nach dem EWR-Nein". Watson (in German). Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Geschäft Ansehen". Federal Assembly. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Council conclusions on EU relations with EFTA countries" (PDF). Council of the European Union. 14 December 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2010. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS EU Relations with the Principality of Andorra, the Principality of Monaco and the Republic of San Marino Options for Closer Integration with the EU

- ^ "Norge sier nei til nye mikrostater i EØS". 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Innlegg på møte i Stortingets europautvalg". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Norway. 28 January 2013. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ "Eide: Bedre blir det ikke". 21 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b Aalberg Undheim, Eva (8 December 2012). "Regjeringa open for diskutere EØS-medlemskap for mikrostatar" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "La Norvegia chiude le porte a San Marino" (PDF). La Tribuna Sammarinese. 3 January 2013. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ^ "EU Relations with the Principality of Andorra, the Principality of Monaco and the Republic of San Marino: Options for their participation in the Internal Market". European Commission. 18 November 2013. Archived from the original on 23 December 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ^ Colson, Thomas (2 August 2018). "Michael Gove has been privately pushing a plan to keep Britain in the single market". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 10 September 2022. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ "Leaving the EU – RESEARCH PAPER 13/42" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 1 July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "The Latest: Lithuania says UK must say if decision is final". CNBC. 27 June 2016. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2016 – via Associated Press.

- ^ Norway's European affairs minister, Elisabeth Vik Aspaker, told the newspaper Aftenposten: "It's not certain that it would be a good idea to let a big country into this organisation. It would shift the balance, which is not necessarily in Norway's interests". Wintour, Patrick (9 August 2016). "Norway may block UK return to European Free Trade Association | World news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ Wilkinson, Michael (17 January 2017). "Theresa May confirms Britain will leave Single Market as she sets out 12-point Brexit plan". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ Wintour, Patrick (3 September 2017). "Efta court chief visits UK to push merits of 'Norway model'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 December 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Sturgeon hints the Scottish Government could seek Norway-style EU relationship". 17 November 2016. Archived from the original on 18 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ^ Johnson, Simon (16 March 2017). "Iceland: Scotland could not start applying for EFTA until after independence". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "No EU regulation alignment post-Brexit, warns Sajid Javid". ITV News. 18 January 2020. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "UK Government can't guarantee 'frictionless trade' after Brexit, admits Michael Gove". belfasttelegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ Payne, Sebastian (2 February 2020). "Boris Johnson to reject regulatory alignment in EU trade talks". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2020.

- ^ "Free Movement of Persons | European Free Trade Association". Efta.int. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Hauge, Lars-Erik. "Norway's financial contribution". eu-norway.org. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

10.08.2016

- ^ Ekman, Ivar (27 October 2005). "In Norway, EU pros and cons (the cons still win)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "House of Commons Hansard Debates for 8 Jun 2005 (pt 17)". Publications.parliament.uk. 8 June 2005. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ "Influencing the EU – EEA Decision Shaping | European Free Trade Association". Efta.int. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- ^ Internal preparatory discussions on framework for future relationship – Governance of an International Agreement p. 14 Archived 24 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The EEA Judicial System and the Supreme Courts of the EFTA States" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 April 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

External links

[edit]- European Economic Area

- 1993 in Belgium

- 1993 in the European Union

- 1994 establishments in Europe

- Foreign relations of Croatia

- Foreign relations of the European Union

- Foreign relations of Iceland

- Foreign relations of Liechtenstein

- Foreign relations of Norway

- Foreign relations of Switzerland

- Iceland–European Union relations

- Intergovernmental organizations established by treaty

- International organizations based in Europe

- International relations

- Multi-speed Europe

- Organizations established in 1994

- Norway–European Union relations

- Switzerland–European Union relations

- Treaties concluded in 1993

- Treaties entered into force in 1994

- United Kingdom and the European Union

- March 1993 events in Europe