Basilica of Saint-Denis

| Basilica of Saint-Denis | |

|---|---|

Basilique Saint-Denis (French) | |

West façade of Saint-Denis | |

| |

| 48°56′08″N 2°21′35″E / 48.93556°N 2.35972°E | |

| Location | Saint-Denis, France |

| Denomination | Catholic |

| Tradition | Roman Rite |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1135 |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Saint-Denis |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Pascal Delannoy |

The Basilica of Saint-Denis (French: Basilique royale de Saint-Denis, now formally known as the Basilique-cathédrale de Saint-Denis[1]) is a large former medieval abbey church and present cathedral in the commune of Saint-Denis, a northern suburb of Paris. The building is of singular importance historically and architecturally as its choir, completed in 1144, is widely considered the first structure to employ all of the elements of Gothic architecture.[2][3]

The basilica became a place of pilgrimage and a necropolis containing the tombs of the kings of France, including nearly every king from the 10th century to Louis XVIII in the 19th century. Henry IV of France came to Saint-Denis formally to renounce his Protestant faith and become a Catholic. The queens of France were crowned at Saint-Denis, and the regalia, including the sword used for crowning the kings and the royal sceptre, were kept at Saint-Denis between coronations.[4]

The site originated as a Gallo-Roman cemetery in late Roman times. The archaeological remains still lie beneath the cathedral; the graves indicate a mixture of Christian and pre-Christian burial practices.[5] Around the year AD 475, St. Genevieve purchased some land and built Saint-Denys de la Chapelle. In 636, on the orders of Dagobert I, the relics of Saint Denis, a patron saint of France, were reinterred in the basilica. The relics of St-Denis, which had been transferred to the parish church of the town in 1795, were brought back again to the abbey in 1819.[6]

In the 12th century, the Abbot Suger rebuilt portions of the abbey church using innovative structural and decorative features. In doing so, he is said to have created the first truly Gothic building.[7] In the following century the master-builder Pierre de Montreuil rebuilt the nave and the transepts in the new Rayonnant Gothic style.[4]

The abbey church became a cathedral on the formation of the Diocese of Saint-Denis by Pope Paul VI in 1966 and is the seat of the Bishop of Saint-Denis, currently (since 2009) Pascal Delannoy. Although known as the "Basilica of St Denis", the cathedral has not been granted the title of Minor Basilica by the Vatican.[8]

The 86-metre (282-foot) tall spire, dismantled in the 19th century, is to be rebuilt. The project initiated more than 30 years ago, was decided in 2018 with a signed agreement,[9] with initial restoration work beginning in 2022. From 2025, the building project will commence, with visitors of the cathedral being able to observe the building works as part of their tour.[10] The project is planned to be completed by 2029, with a cost of 37 million euro.[11]

History

[edit]Early churches

[edit]The cathedral is on the site where Saint Denis, the first bishop of Paris, is believed to have been buried. According to the "Life of Saint Genevieve", written in about 520, he was sent by Pope Clement I to evangelise the Parisii. He was arrested and condemned by the Roman authorities. Along with two of his followers, the priest Rusticus and deacon Eleutherius, he was decapitated on the hill of Montmartre in about 250 AD. According to the legend, he is said to have carried his head four leagues to the Roman settlement of Catulliacus, the site of the current church, and indicated that it was where he wanted to be buried. A martyrium or shrine-mausoleum was erected on the site of his grave in about 313 AD, and was enlarged into a basilica with the addition of tombs and monuments under Saint Genevieve. These including a royal tomb, that of Aregonde, the wife of King Clothar I.[6][12]

-

Dagobert I visiting the construction site of the Abbey of St. Denis (painted 1473)

-

Clovis II visiting Saint Denis (painted in 15th c.)

Dagobert I, King of the Franks (reigned 628 to 637), transformed the church into the Abbey of Saint Denis, a Benedictine monastery in 632.[13] It soon grew to a community of more than five hundred monks, plus their servants.[14]

Dagobert also commissioned a new shrine to house the saint's remains, which was created by his chief councillor, Eligius, a goldsmith by training. An early vita of Saint Eligius describes the shrine:

:Above all, Eligius fabricated a mausoleum for the holy martyr Denis in the city of Paris with a wonderful marble ciborium over it marvelously decorated with gold and gems. He composed a crest [at the top of a tomb] and a magnificent frontal and surrounded the throne of the altar with golden axes in a circle. He placed golden apples there, round and jeweled. He made a pulpit and a gate of silver and a roof for the throne of the altar on silver axes. He made a covering in the place before the tomb and fabricated an outside altar at the feet of the holy martyr. So much industry did he lavish there, at the king's request, and poured out so much that scarcely a single ornament was left in Gaul, and it is the greatest wonder of all to this very day.[15]

The Carolingian church

[edit]-

Walls of the crypt built by the Abbot Hilduin (9th century)

-

Capital of a column in the Carolingian crypt

-

Earliest sarcophagi in the crypt

During his second coronation at Saint-Denis, King Pepin the Short made a vow to rebuild the old abbey.[16] The first church mentioned in the chronicles was begun in 754 and completed under Charlemagne, who was present at its consecration in 775. By 832 the Abbey had been granted a remunerative whaling concession on the Cotentin Peninsula.[17]

According to one of the Abbey's many foundation myths a leper, who was sleeping in the nearly completed church the night before its planned consecration, witnessed a blaze of light from which Christ, accompanied by St Denis and a host of angels, emerged to conduct the consecration ceremony himself. Before leaving, Christ healed the leper, tearing off his diseased skin to reveal a perfect complexion underneath. A mis-shapen patch on a marble column was said to be the leper's former skin, which stuck there when Christ discarded it. Having been consecrated by Christ, the fabric of the building was itself regarded as sacred.[18]

Most of what is now known about the Carolingian church at St Denis resulted from a lengthy series of excavations begun under the American art historian Sumner McKnight Crosby in 1937.[19] The structure altogether was about eighty meters long, with an imposing facade, a nave divided into three sections by two rows of marble columns, a transept, and apse and at the east end. During important religious celebrations, the interior of the church was lit with 1250 lamps.[20] Beneath the apse, in imitation of St. Peter's in Rome, a crypt was constructed, with a Confession, or martyr's chapel, in the center. Inside this was a platform on which the sarcophagus of Denis was displayed, with those of his companions Rusticus and Eleutherus on either side. Around the platform was a corridor where pilgrims could circulate, and bays with windows. Traces of painted decoration of this original crypt can be seen in some of the bays.[20]

The crypt was not large enough for the growing number of pilgrims who came, so in about 832 the abbot Hilduin built a second crypt, to the west of the first, and a small new chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary was constructed next to the apse. The new crypt was extensively rebuilt under Suger in the 12th century.[20]

Suger and the Early Gothic Church (12th century)

[edit]-

Abbot Suger depicted in the Tree of Jesse window (19th c.)

-

Louis VI of France visiting St. Denis (14th century illustration)

-

The Oriflamme (top left), or battle flag of French kings, was kept at Saint Denis.

-

King Philip II of France receives the Oriflamme from the bishop before going to war (13th c., 1841 painting)

Abbot Suger (c. 1081 – 1151), the patron of the rebuilding of the Abbey church, had begun his career in the church at the age of ten, and rose to become the Abbot in 1122. He was a school companion and then confidant and minister of Louis VI and then of his son Louis VII, and was a regent of Louis VII when the King was absent on the Crusades.[20] He was an accomplished fund-raiser, acquiring treasures for the cathedral and collecting an enormous sum for its rebuilding. In about 1135 he began reconstructing and enlarging the abbey. In his famous account of the work undertaken during his administration, Suger explained his decision to rebuild the church, due to the decrepit state of the old structure and its inability to cope with the crowds of pilgrims visiting the shrine of St Denis.

In the 12th century, thanks largely to Suger, the Basilica became a principal sanctuary of French Royalty, rivalling Reims Cathedral, where the kings were crowned. The Abbey also kept the regalia of the coronation, including the robes, crowns and sceptre.[21] Beginning in 1124, and until the mid-15th century, the kings departed for war carrying the oriflamme, or battle flag, of St. Denis, to give the King the protection of the Saint. It was taken to the Abbey only when France was in danger. The flag was retired in 1488, when the Parisians opened the gates of Paris to invading English and Burgundian armies.

First Phase: the west front (1135–1140)

[edit]Suger began his rebuilding project at the western end of St Denis, demolishing the old Carolingian facade with its single, centrally located door. He extended the old nave westwards by an additional four bays and added a massive western narthex, incorporating a new façade and three chapels on the first floor level.

In the new design, massive vertical buttresses separated the three doorways and horizontal string-courses and window arcades clearly marked out the divisions. This clear delineation of parts was to influence subsequent west façade designs as a common theme in the development of Gothic architecture and a marked departure from the Romanesque. The portals themselves were sealed by gilded bronze doors, ornamented with scenes from Christ's Passion. They clearly recorded Suger's patronage with the following inscription:

On the lintel below the great tympanum showing the Last Judgement, beneath a carved figure of the kneeling Abbot, was inscribed the more modest plea;

Receive, stern Judge, the prayers of your Suger, Let me be mercifully numbered among your sheep.

Second Phase: the new choir, (1140–1144)

[edit]Suger's western extension was completed in 1140 and the three new chapels in the narthex were consecrated on 9 June of that year, but the Romanesque nave between was yet unchanged. He wrote about the new narthex at the west end and proposed chapels at the east: "Once the new rear part is joined to the part in front, the church shines with its middle part brightened. For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright, and bright is the noble edifice which is pervaded by the new light."[22]

Suger's great innovation in the new choir was the replacement of the heavy dividing walls in the apse and ambulatory with slender columns, so that the interior of that part of the church was filled with light. He described "A circular string of chapels, by virtue of which the whole church would shine with the wonderful and uninterrupted light of most luminous windows, pervading the interior beauty."[22] One of these chapels was dedicated to Saint Osmanna, and held her relics.[23]

Suger's masons drew on elements which evolved or had been introduced to Romanesque architecture: the rib vault with pointed arches, and exterior buttresses which made it possible to have larger windows and to eliminate interior walls. It was the first time that these features had all been drawn together; and the new style evolved radically from the previous Romanesque architecture by the lightness of the structure and the unusually large size of the stained glass windows.[24]

The new architecture was full of symbolism. The twelve columns in the choir represented the twelve Apostles, and the light represented the Holy Spirit. Like many French clerics in the 12th century AD, he was a follower of Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, a 6th century mystic who equated the slightest reflection or glint with divine light. Suger's own words were carved in the nave: "For bright is that which is brightly coupled with the bright/and bright is the noble edifice which is pervaded by the new light."[25] Following Suger's example, large stained glass windows filling the interior with mystical light became a prominent feature of Gothic architecture.[22]

Two different architects, or master masons, were involved in the 12th century rebuilding.[26] Both remain anonymous but their work can be distinguished on stylistic grounds. The first, who was responsible for the initial work at the western end, favoured conventional Romanesque capitals and moulding profiles with rich and individualised detailing. His successor, who completed the western facade and upper storeys of the narthex, before going on to build the new choir, displayed a more restrained approach to decorative effects, relying on a simple repertoire of motifs, which may have proved more suitable for the lighter Gothic style that he helped to create.[27]

The Portal of Valois was the last of the Gothic structures planned by Suger. It was designed for the original building, but was not yet begun when Suger died in 1151. In the 13th century it was moved to the end of the new transept on the north side of the church.[28] The sculpture of the portal includes six standing figures in the embracements and thirty figures in the voussures, or arches, over the doorway, which probably represent the Kings of the Old Testament. The scene in the Tympanum over the doorway depicts the martyrdom of Saint Denis. In their realism and finesse, they were a landmark in Gothic sculpture.[29]

The new structure was finished and dedicated on 11 June 1144, in the presence of the King.[30] The Abbey of St Denis thus became the prototype for further building in the royal domain of northern France. Through the rule of the Angevin dynasty, the style was introduced to England and spread throughout France, the Low Countries, Germany, Spain, northern Italy and Sicily.[31][32]

Reconstruction of the Nave – the Rayonnant style – beginning of the Royal Necropolis (13th century)

[edit]-

The glazed triforium (center level) and upper clerestory, where windows fill almost the entire wall, a prominent feature of Rayonnant Gothic. (present windows from 19th c.)

-

Rayonnant rose window in the north transept

Suger died in 1151 with the Gothic reconstruction incomplete. In 1231, Abbot Odo Clement began work on the rebuilding of the Carolingian nave, which remained sandwiched incongruously between Suger's Gothic works to the east and west. Both the nave and the upper parts of Suger's choir were replaced in the Rayonnant Gothic style. From the start it appears that Abbot Odo, with the approval of the Regent Blanche of Castile and her son, the young King Louis IX, planned for the new nave and its large crossing to have a much clearer focus as the French 'royal necropolis', or burial place. That plan was fulfilled in 1264 under Abbot Matthew of Vendôme when the bones of 16 former kings and queens were relocated to new tombs arranged around the crossing, eight Carolingian monarchs to the south and eight Capetians to the north.[33] These tombs, featuring lifelike carved recumbent effigies or gisants lying on raised bases, were badly damaged during the French revolution though all but two were subsequently restored by Viollet le Duc in 1860.

The dark Romanesque nave, with its thick walls and small window-openings, was rebuilt using the very latest techniques, in what is now known as Rayonnant Gothic. This new style, which differed from Suger's earlier works as much as they had differed from their Romanesque precursors, reduced the wall area to an absolute minimum. Solid masonry was replaced with vast window openings filled with brilliant stained glass (all destroyed in the Revolution) and interrupted only by the most slender of bar tracery—not only in the clerestory but also, perhaps for the first time, in the normally dark triforium level. The upper facades of the two much-enlarged transepts were filled with two spectacular 12m-wide rose windows.[34] As with Suger's earlier rebuilding work, the identity of the architect or master mason remains unknown. Although often attributed to Pierre de Montreuil, the only evidence for his involvement is an unrelated document of 1247 which refers to him as 'a mason from Saint-Denis'.[35]

15th–17th century

[edit]-

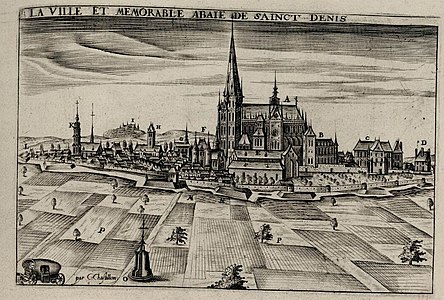

The cathedral in 1655 by Claude Chastillon

-

Henry IV of France renounces Protestantism in 1593 at Saint-Denis by Nicolas Baullery

During the following centuries, the cathedral was pillaged twice; once during the Hundred Years War (1337–1453) and again during the Wars of Religion (1562–1598). Damage was largely limited to broken tombs and precious objects stolen from the altars and treasury. Many modifications were made under Marie de' Medici and later royal families. These included the construction of chapel adjoining the north transept to serve as a tomb for the monarchs of the Valois Dynasty (later demolished). A plan of c. 1700 by Félibien shows the Valois Chapel, a large mortuary chapel in the form of a domed colonnaded "rotunda", adjoining the north transept of the basilica and containing the tomb of the Valois.[36] and the display of the skeleton of a baleine whale in the nave in 1771. Greater harm was done with the removal of the early Gothic column-statues which Suger had used to decorate the west front. (They were replaced with replicas in the 19th century).[37] In 1700, reconstruction began of the monastic buildings adjacent to the church. This was not completed until the mid-18th century. Into these buildings Napoleon installed a school for the daughters of members of the French Legion of Honour, which still is in operation.[38]

The French Revolution and Napoleon

[edit]-

The looting of the church in 1793, by Friedrich Staffnick

-

The violation of the royal tombs in 1793 depicted by Hubert Robert

Due to its connections to the French monarchy and proximity to Paris, the abbey of Saint-Denis was a prime target of revolutionary vandalism. On Friday, 14 September 1792, the monks celebrated their last services in the abbey church; the monastery was dissolved the next day. The church was used to store grain and flour.[39] In 1793, the National Convention, the revolutionary government, ordered the violation of the sepulchres and the destruction of the royal tombs, but agreed to create a commission to select those monuments which were of historical interest for preservation. In 1798, these were transferred to the chapel of the Petit-Augustins, which later became the Museum of French Monuments.[40]

Most of the medieval monastic buildings were demolished in 1792. Although the church itself was left standing, it was profaned, its treasury confiscated and its reliquaries and liturgical furniture melted down for their metallic value. Some objects, including a chalice and aquamanile donated to the abbey in Suger's time, were successfully hidden and survive to this day. The jamb figures of the façade representing Old Testament royalty, mistakenly identified as images of royal French kings and queens, were removed from the portals and the tympana sculpture defaced.

In 1794, the government decided to remove the lead tiles from the roof, to melt them down to make bullets. This left the interior of the church badly exposed to the weather.[39]

19th century – reconstruction and renovation

[edit]-

The left tower, completed, damaged and removed in the 1840s

-

The two-tower plan of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, never built

The church was reconsecrated by Napoléon in 1806, and he designated it as the future site for his own tomb and those of his intended dynasty.[40] He also ordered the construction of three chapels to honour the last French kings, created a chapel under the authority of his uncle, Cardinal Fesch, which was decorated with richly-carved choir stalls and marquetry from the Château de Gaillon. (See "Choir Stalls" section below).[39]

After Napoleon's downfall, the ashes of the previous king, Louis XVI, were ceremoniously moved from the cemetery of the Madeleine to Saint-Denis. The last king to be entombed in Saint-Denis was Louis XVIII in 1824.

In 1813 François Debret was named the chief architect of the cathedral; he proceeded, over thirty years, to repair the Revolutionary damage. He was later best known for his design of the Salle Le Peletier, the primary opera house of Paris before the Opéra Garnier in 1873. He replaced the upper stained glass windows in the nave with depictions of the historic kings of France, and added new windows to the transept depicting the renovation, and the July 1837 visit to the Cathedral of King Louis Philippe. On 9 June, the spire of the tower was struck by lightning and destroyed. Debret rapidly put into place a new spire, but he did not fully understand the principles of Gothic architecture. He made errors in his plans for the new structure, which resulted in the spire and tower collapsing under their own weight in 1845.[41][42]

Debret resigned and was replaced by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who had the support of Prosper Mérimée, the French author who led campaign for the restoration of ruined Gothic architecture in France. Viollet-le-Duc continued working on the Abbey until his death in 1879, and replaced many of the creations conceived by Debret. Viollet-le-Duc focused on the tombs, rearranging and transforming portions of the interior into a vast museum of French sculpture. In the 1860s Emperor Napoleon III asked Viollet-le-Duc to construct an imperial section in the crypt for him and his dynasty, but he was deposed and went into exile before it was begun.[40][39]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]-

West portals before cleaning (2011)

In 1895, when the chapter created by Napoleon was dissolved, the church lost its cathedral rank and reverted to being a parish church. It did not become a cathedral again until 1966, with the creation of the new diocese of Saint-Denis. The formal title is now the "Baslilique-cathédrale de Saint-Denis".[43]

In December 2016, 170 years after the north tower's dismantlement and following several false starts, the Ministry of Culture again proposed its reconstruction after concluding it was technically feasible—albeit without public funding.[44] An association, Suivez la flèche ("Follow the Spire"), chaired by Patrick Braouezec, has since been established to support the reconstruction, with the aim of raising the necessary funds by opening the reconstruction works to the general public, along the model of the Guédelon Castle. In March 2018, the culture ministry signed an accord with the association, officially launching the reconstruction project, with works expected to commence in May 2020.[45][46] A year later, French scholars were still divided on the €25 million proposal to reconstruct the spire.[47] In 2023, hundreds of anonymous graves dating from the 5th to the 14th century were discovered in the Basilica.[48] In the same year, the Basilica's stained glass windows which have been the central focus of a project spanning 25 years, entered the final stage of restoration with a total cost exceeding 2 million euros.[49]

Exterior

[edit]The west front

[edit]-

The west front

-

Tympanum and lintel of the central portal "Last Judgement (c. 1135, restored 1839)

-

The west front after its cleaning

The west front of the church, dedicated on 9 June 1140, is divided into three sections, each with its own entrance, representing the Holy Trinity. A crenellated parapet runs across the west front and connects the towers (still unfinished in 1140), illustrating that the church front was the symbolic entrance to the celestial Jerusalem.[50]

This new façade, 34 metres (112 ft) wide and 20 metres (66 ft) deep, has three portals, the central one larger than those on either side, reflecting the relative width of the central nave and lateral aisles. This tripartite arrangement was clearly influenced by the late 11th century Norman-Romanesque façades of the abbey churches of St Etienne.[22] It also shared with them a three-storey elevation and flanking towers. Only the south tower survives; the north tower was dismantled following a tornado which struck in 1846.

The west front was originally decorated with a series of column statues, representing the kings and queens of the Old Testament. These were removed in 1771 and were mostly destroyed during the French Revolution, though a number of the heads can be seen in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.[50]

The bronze doors of the central portal are modern, but are a faithful reproduction of the original doors, which depicted the Passion of Christ and the Resurrection.[50]

One other original feature was added by Suger's builders; a rose window over the central portal.[22] Although small circular windows (oculi) within triangular tympana were common on the west facades of Italian Romanesque churches, this was probably the first example of a rose window within a square frame, which was to become a dominant feature of the Gothic facades of northern France (soon to be imitated at Chartres Cathedral and many others).[51]

Chevet and transepts

[edit]-

The apse, or east end of the cathedral, in 1878

-

North transept (left) and north nave walls and buttresses (19th c.)

-

The Rayonnant south transept

-

South side of the nave, with buttresses and chapels

The chevet, at the east end of the cathedral, was one of the first parts of the structure rebuilt into the Gothic style. The work was commissioned by Abbot Suger in 1140 and completed in 1144. It was considerably modified under the young King Louis IX and his mother, Blanche of Castille, the Regent of the Kingdom, beginning in 1231. The apse was built much higher, along with the nave. Large flying buttresses were added to the chevet, to support the upper walls, and to make possible the enormous windows installed there. The masons used the same engineering concept that was used at the Abbey of Saint-Martin-des-Champs to support the large chapel windows.[52] At the same time, the transept was enlarged and given large rose windows in the new rayonnant style, divided into multiple lancet windows topped by trilobe windows and other geometric forms inscribed in circles. The walls of the nave on both sides were entirely filled with windows, each composed of four lancets topped by a rose, filling the entire space above the triforium. The upper walls, like the chevet, were supported by flying buttresses whose bases were placed between the chapels alongside the nave.[53]

North and south portals

[edit]-

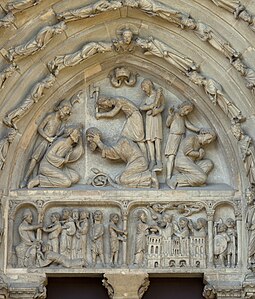

Sculpture of the Porte de Valois, or north portal

-

The south portal and sculpture

-

Detail of the south portal sculpture

The Porte de Valois, or north portal, was originally built in the 12th century, near the end of Suger's life, then rebuilt at the end of the north transept in the 13th century. According to Suger, the original entrance on the north did not have sculpture, but mosaic, which Suger replaced by sculpture in 1540. It is considered an important step in the history of Gothic sculpture, because of the skill of the carving, and the lack of rigidity of the figures. There are six figures in the embrasures and thirty figures in the voussures, or arches above the door, which represent kings, probably those of the Old Testament, while the tympanum over the door illustrates the martyrdom of Saint-Denis and his companions Eleuthere and Rusticus. This portal was among the last works commissioned by Suger; he died in 1151, before it was completed.[28] The original sculpture that was destroyed in the Revolution was replaced with sculpture from the early 19th century, made by Felix Brun.[54]

The tympanum of the south portal illustrates the last days of the Denis and his companions before their martyrdom. The piedroits are filled with medallions representing the labours of the days of month.[54]

Interior

[edit]The nave and choir

[edit]-

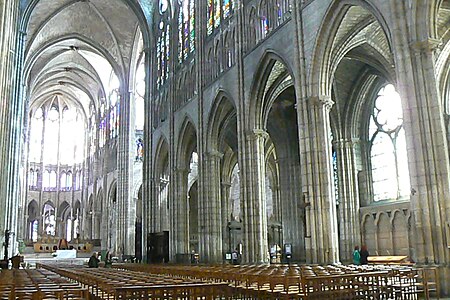

The nave and choir

-

The elevation of the nave, with glass-filled triforium and upper windows

-

The vaults in the transept

The nave, the portion to the west of the church reserved for ordinary worshippers, and the choir, the portion to the east reserved for the clergy, were rebuilt into the Gothic style in the 13th century, after the apse at the east and the west front. Like the other Gothic churches in the Ile-de-France, its walls had three levels; large arcades of massive pillars on the ground floor; a narrow triforium or passageway midway up the wall; originally windowless; and a row of high windows the clerestory, above. Slender columns rose from the pillars up the walls to support the four-part rib vaults. As a result of the Rayonnant reconstruction in the triforium was given windows, and the upper walls were entirely filled with glass, which reached upward into the arches of the vaults, flooding the church with light.[55]

The disambulatory and chapels

[edit]-

The ambulatory (1140–1144)

-

disambulatory

-

Disambulatory and chapels

-

The axial chapel of the Virgin (12th c.)

The chevet had been constructed by Suger in record time, in just four years, between 1140 and 1144, and was one of the first great realisations of Gothic architecture. The double disambulatory is divided not by walls but by two rows of columns, while the outside walls, thanks to buttresses on the exterior, are filled with windows. The new system allowed light to pass into the interior of the choir. The disambulatory connects with the five radiating chapels at the east end of the cathedral, which have their own large windows. To give them greater unity, the five chapels share the same system of vaulted roofs. To make the walls between the chapels even less visible, they are masked with networks of slender columns and tracery.[54]

The apse with its two ambulatories and axial chapels was extensively rebuilt in the 12th century, to connect harmoniously with the new and larger nave, but a major effort was made to save the early Gothic features created by Suger, including the double disambulatory with its large windows. To accomplish this, four large pillars were installed in the crypt to support the upper level, and the walls of the first traverse of the sanctuary were placed at an angle to connect with the wider transept.[56]

The basilica retains stained glass of many periods (although most of the panels from Suger's time have been removed for long-term conservation and replaced with photographic transparencies), including exceptional modern glass, and a set of 12 misericords.

Crypt and royal tombs

[edit]-

The archeological crypt (8th century) rebuilt by Suger (12th c.), now contains the simple black marble tombs of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette

-

Carolingian decoration from the early crypt

-

Tomb of Dagobert I, first King buried at St. Denis remade in the 13th century

The role of St. Denis as the necropolis of French kings formally began under Hugh Capet (987–996), but the tombs of several earlier kings were already located there. The site was chosen because of its association with St. Denis, the first Bishop of Paris and one of the earliest Christian leaders in France, who was buried there[57] All but three of the monarchs of France from the 10th century until 1793 have their remains here. The remains of some monarchs, including Clovis I (465–511), were moved to St. Denis from other churches.

The crypt beneath the church is divided into two sections; the older, called archeological crypt, is located under the transept, and was originally built in about 775 AD, when the abbey was reconstructed by Abbot Fuldiad. It had a disambulatory, passage which allowed pilgrims to circulate around the relics of Saint Denis and his companions on display in the center. It was lit by alternating small windows in the walls and lamps placed in niches.

The crypt was rebuilt and extended eastward by Suger. The walls were decorated with blind arches, divided by columns whose capitals illustrate Biblical scenes and scenes from the life of St. Denis. Thirty-nine of the original Romanesque sixty-two capitals are still in place. Sugar constructed a new disambulatory connected with radiating chapels.[58]

During the reign of Henry IV, the central portion of this crypt was devoted the Bourbon dynasty, but the tombs themselves were simple lead coffins in wood cases. The effigies of many of the kings and queens are on their tombs, but during the French Revolution their bodies were thrown out of their coffins, dumped into three trenches and covered with lime to destroy them. The older monarchs were removed in August 1793 to celebrate the revolutionary Festival of Reunion, the Valois and Bourbon monarchs in October 1793 to celebrate the execution of Marie Antoinette.[59] Preservationist Alexandre Lenoir saved many of the monuments by claiming them as artworks for his Museum of French Monuments. The bodies of several Plantagenet monarchs of England were likewise removed from Fontevraud Abbey during the French Revolution. Napoleon Bonaparte reopened the church in 1806, but left the royal remains in their mass graves. In 1817 the restored Bourbons ordered the mass graves to be opened, but only portions of three bodies remained intact. The remaining bones from 158 bodies were collected into an ossuary in the crypt of the church, behind marble plates bearing their names.[59]

In later years, tombs were placed along the aisles that surrounded around the choir and the nave. In the 13th century King Louis IX (Saint Louis) commissioned a number of important tombs of earlier kings and French historical figures, whose remains were collected from other churches. These included the tombs of Clovis I, Charles Martel, Constance of Castile, Pepin the Short, Robert the Pious and Hugh Capet (which disappeared during the Revolution). The new tombs were all made in the same style and costume, with a reposing figure holding a staff, to illustrate the continuity of the French Monarchy.[58]

-

Tomb of Louis XII and Anne of Brittany, (c. 1515)

-

Tomb of Catherine de Medici and Henry II of France (1559)

-

Funeral urn of Francois I by sculptor Pierre Bontemps (1556)

The tombs of the Renaissance expressed are theatrical and varied. The largest is that of Louis XII (died 1515) and his wife, Anne of Brittany (died 1514). It takes the form of a white marble temple filled and surrounded with figures. Inside it, the King and Queen are depicted realistically in their dying agonies, Allegorical figures seated around the temple depict the virtues of the King and Queen. On the roof of the tomb, the King and Queen are shown again, kneeling and calmly praying, celebrating their victory over death, thanks to their virtues.[60]

The monument to Henry II of France and Catherine de Medici (1559) followed a similar format; a Roman temple, in this case designed by the celebrated Renaissance architect Primatrice with sculpture on the roof depicting the King and Queen in prayer. The King places his hand on his heart illustrating his Catholic faith a period of religious conflicts.[60]

In the 19th century, following the restoration of the monarchy, Louis XVIII had the remains of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette brought to St. Denis. The body of the Dauphin, who died of illness and neglect at the hands of his revolutionary captors, was buried in an unmarked grave in a Parisian churchyard near the Temple. During Napoleon's exile in Elba, the restored Bourbons ordered a search for the corpses of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. They were found on 21 January 1815, brought to Saint-Denis and placed in the archeologi crypt. Their tombs are covered with black marble slabs installed in 1975.[61]

Louis XVIII, upon his death in 1824, was buried in the centre of the crypt, near the graves of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette. The coffins of royal family members who died between 1815 and 1830 were also placed in the vaults. Under the direction of architect Viollet-le-Duc, church monuments that had been taken to the Museum of French Monuments were returned to the church. The corpse of Louis VII, who had been buried at Barbeau Abbey and whose tomb had not been touched by the revolutionaries, was brought to Saint-Denis and buried in the crypt. In 2004, the mummified heart of the Dauphin, the boy who would have been Louis XVII, verified to be authentic by DNA testing, was placed in a crystal vase and sealed into the wall of the crypt.[62]

Sacristy

[edit]-

The Sacristy, rebuilt in 1812

The Sacristy, the room where the clergy traditionally donned their vestments, was transformed by the architect Jacques Cellerier in 1812 into a Neo-classical gallery of murals which depict scenes from the history of the cathedral. A work added to the Sacristy is "Allegory of the Divine Word", a painting by Simon Vouet, which originally had been commissioned by Louis XIII for the retable of the Chateau of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. It was acquired for the cathedral by the administration of national monuments in 1993. The wall cases also display a selection of precious objects from the cathedral's collection.[39]

Art and decoration

[edit]Stained glass

[edit]-

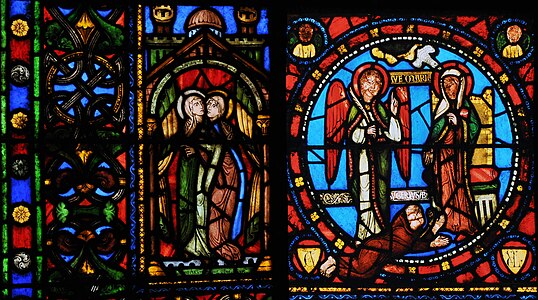

"Childhood of Christ", (12th c., Saint Mary Axis chapel)

-

Detail from the 12th century Life of Christ window, Axis chapel

-

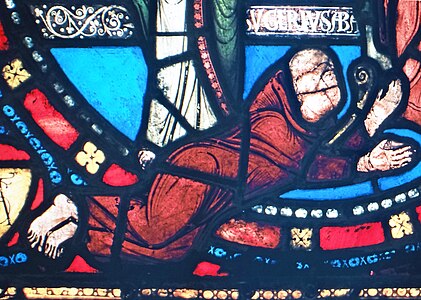

Detail of The Annunciation pane in the "Chilhood of Christ" window, Suger prostrated at the feet of the Virgin Mary (12th c.)

-

Detail of Suger kneeling in the lower right corner of Tree of Jesse window

Abbot Suger commissioned a large amount of stained glass for the new chevet, but only very small amount of the original glass from the time of Suger survived intact. In the 19th century it was collected by Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, and was integrated into windows in the chevet. Original glass includes the figure of Suger prostrating himself at the feet of the Virgin Mary, in the window called "The Childhood of Christ"; and kneeling in the lower right corner of the Tree of Jesse, illustrating the genealogy of Christ, in the Axis chapel; the "Allegories of Saint Paul" and "The Life of Moses" in the fourth radiating chapel on the north; "The vision of Ezekiel under the sign of tau", originally from a group illustrating the Passion of Christ, in the fourth rayonnant chapel on the south, in the left bay and third register.[63] Another piece of original window from Suger's time, depicting mythical Griffonsa a symbol of Paradise, is found in the second radiating chapel on the north. Other scenes which Suger described, showing the pilgrimage of Charlemagne and the Crusades, have disappeared.[63]

-

"Kings and Queens of France" (19th c.)

-

"The visit of King Louis-Philippe to Saint-Denis in 1837"

Much of the current stained glass dates to the 19th century, as the church began to be restored from the damage of the Revolution. The architect François Debret designed the first Neo-Gothic windows of the nave in 1813. these include the upper windows of the nave, which represent the kings and queens of France. Later upper windows of the south transept depict the restoration of the church, and particularly the visit there of Louis Philippe I, the last king of France, in 1837. This large group of windows was designed by the painter Jean-Baptiste Debret, the brother of the architect.[64]

Sculpture

[edit]-

Detail of the north portal sculpture; the martyrdom of Saint Denis, Eleuthere and Rustique (12th c.)

-

Piedroits, or column statues, of the north portal. (12th c.)

-

Tomb of Clovis I and his son, Childebert I

-

Tomb of King Dagobert (13th century)

-

Memorial to King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette, sculptures (1830) by Edme Gaulle and Pierre Petitot

-

Ementrude of Orleans, wife of Charles II of France

-

Bust of Charles V of France

-

Battle scene on the tomb of François I (16th c.)

The new west front sculpture of St. Denis had an important influence on Gothic style. The influential features of the new façade include the tall, thin statues of Old Testament prophets and kings attached to columns (jamb figures) flanking the portals (destroyed in 1771 but recorded in Montfaucon's drawings). These were also adopted at the cathedrals of Paris and Chartres, constructed a few years later, and became a feature of almost every Gothic portal thereafter.[65]

The statues on the portal of the Valois, on the transept of the Saint Denis, made in 1175, have very elongated and expressive figures, and also had an important effect on Gothic sculpture. They were the opposite of the more restrained and dignified figures of Chartres Cathedral, made about the same time.[65]

Above the doorways, the central tympanum was carved with Christ in Majesty displaying his wounds with the dead emerging from their tombs below. Scenes from the martyrdom of St Denis were carved above the south (right hand) portal, while above the north portal was a mosaic (lost), even though this was, as Suger put it 'contrary to the modern custom'. Of the original sculpture, very little remains, most of what is now visible being the result of rather clumsy restoration work in 1839.[66] Some fragments of the original sculptures survive in the collection of the Musée de Cluny.

Choir stalls

[edit]-

The choir stalls (16th c.)

-

Detail of carving and marquetry of the choir stalls

-

Misericord on a choir stall

The choir stalls, the seats reserved for the clergy, have particularly fine carvings, particularly on the misericord, the small seat on each stall on which the clergy could rest when standing for long periods of time. The stalls were made in the 16th century, and were originally located in the high chapel of the Chateau de Gaillon in the Eure Department. In 1805 Napoleon Bonaparte decided to create three new chapels at Saint-Denis, as well as a chapter of bishops under the authority of his uncle, Cardinal Fesch. The stalls were moved to Saint-Denis and installed for their use. Besides the carved wood, the stalls are decorated with elaborate multi-coloured religious scenes in marquetry.[39]

Organ

[edit]-

The organ of the cathedral (19th c.)

-

Detail of the organ decoration

The organ is located on the tribune, at the west of the nave. An organ is recorded as existing at the basilica in 1520. A later organ, made by Crespin Carlier, is recorded in 1520, but this instrument was destroyed during the French Revolution. The church re-opened in 1806 without an organ. A competition was held in 1833 to find a new builder. It was won by Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, age twenty-three, and was his first organ. It was completed in 1843, and launched his career as an organ-maker.[67]

It contains numerous innovations introduced in the romantic area, in particular the very first Barker lever. With three manuals and pedals, it is protected by the Monument historique label. It was restored in 1901 by Charles Mutin, and between 1983 and 1987 by Jean-Loup Boisseau and Bertrand Cattiaux. Pierre Pincemaille, sole titular organist for 30 years (between 1987 and 2018), held many recitals (between 1989 and 1995, then between 2014 and 2017), and recorded eight CDs using this instrument.[67]

Treasury

[edit]The cathedral contained an extensive treasury, mainly constituted by the Abbot Suger. It contained crowns (those of Charlemagne, Saint Louis, and Henry IV of France), a cross, and liturgical objects.[citation needed]

Burials

[edit]

Kings

[edit]All but five of the kings of France were buried in the basilica (with Charlemagne, Philip I, Louis XI, Charles X, & Louis Philippe I buried elsewhere), as well as a few other monarchs. The remains of the early monarchs were removed from the destroyed Abbey of St Genevieve. Some of the more prominent monarchs buried in the basilica are:

- Clovis I (466–511)

- Childebert I (496–558)

- Aregund (515/520–580)

- Fredegund (third wife of Chilperic I), (died 597)

- Dagobert I (603–639)

- Clovis II (634–657)

- Charles Martel (686–741)

- Pepin the Short (714–768) and his wife, Bertrada of Laon (born 710–727, died 783)

- Charles the Bald (823–877) (his brass monument was melted down during the Revolution) and his first wife, Ermentrude of Orléans (823–869)

- Carloman II (866–884)

- Robert II of France (972–1031) and his third wife, Constance of Arles (986–1032)

- Henry I of France (1008–1060)

- Louis VI of France (1081–1137)

- Louis VII of France (1120–1180) and his second wife, Constance of Castile (1140–1160)

- Philip II of France (1165–1223)

- St. Louis IX of France (1214–1270)

- Charles I of Naples (1227–1285), an effigy covers his heart burial

- Philip III of France (1245–1285) and his first wife, Isabella of Aragon, Queen of France (1248–1271)

- Philip IV of France (1268–1314)

- Leo V, King of Armenia (1342–1393) (cenotaph)

- Charles VII, King of France (1403–1461)

- Charles VIII, King of France (1470–1498)

- Louis XII of France (1462–1515)

- Francis I of France (1494–1547)

- Henry II (1519–1559) and Catherine de' Medici (1519–1589)

- Francis II (1544–1560)

- Charles IX (1550–1574) (no monument)

- Henry III (1551–1589), also King of Poland (heart burial monument)

- Henry IV (1553–1610)

- Louis XIII (1601–1643)

- Louis XIV (1638–1715)

- Louis XV (1710–1774)

- Louis XVI (1754–1793) and Marie Antoinette (1755–1793)

- Louis XVII (1785–1795) (only his heart; his body was dumped into a mass grave)

- Louis XVIII (1755–1824)

Other royalty and nobility

[edit]- Blanche of France (daughter of Philip IV)

- Nicolas Henri, Duke of Orléans (1607–1611), son of Henry IV

- Gaston, Duke of Orléans (1608–1660), son of Henry IV

- Marie de Bourbon, Duchess of Montpensier (1605–1627), wife of Gaston

- Marguerite of Lorraine (1615–1672), Duchess of Orléans and second wife of Gaston

- Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans (1627–1693), la Grande Mademoiselle

- Jean Gaston d'Orléans (1650–1652), Duke of Valois

- Marie Anne d'Orléans (1652–1656), Mademoiselle de Chartres

- Henrietta Maria of France (1609–1669), wife of Charles I of Scotland and England

- Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (1640–1701), brother of Louis XIV

- Princess Henrietta of England (1644–1670), first wife of Philippe

- Elisabeth Charlotte of the Palatinate (1652–1722), second wife of Philippe

- Maria Theresa of Spain (1638–1683), consort of Louis XIV

- Louis of France (1661–1711), le Grand Dauphin

- Maria Anna Victoria of Bavaria (1660–1690), Dauphine of France, wife of Louis

- Princess Anne Élisabeth of France (1662), daughter of Louis XIV

- Princess Marie Anne of France (1664), daughter of Louis XIV

- Marie Thérèse of France (1667–1672), daughter of Louis XIV

- Philippe Charles, Duke of Anjou (1668–1671), Duke of Anjou, son of Louis XIV

- Louis François of France (1672), Duke of Anjou, son of Louis XIV

- Philippe II, Duke of Orléans (1674–1723), Regent of France

- Louis of France (1682–1712), Duke of Burgundy

- Marie Adélaïde of Savoy (1685–1712), Duchess of Burgundy

- Louis of France (1704–1705), Duke of Brittany

- Louis of France (1707–1712), Duke of Brittany

- Charles of France (1686–1714), Duke of Berry

- Marie Louise Élisabeth d'Orléans (1695–1719), Duchess of Berry

- Na (not baptized) d'Alençon (1711)

- Charles d'Alençon(1713) Duke of Alençon

- Marie Louise Élisabeth d'Alençon (1714)

- Marie Leszczyńska (1703–1768), consort of Louis XV

- Louise Élisabeth of France (1727–1759), Duchess of Parma

- Henriette of France (1727–1752), daughter of Louis XV and twin of the above

- Louise of France (1728–1733), daughter of Louis XV

- Louis of France (1729–1765), Dauphin of France (only his heart; his body was buried in the Cathedral of Saint-Étienne)

- Infanta Maria Teresa Rafaela of Spain (1726–1746), first wife of above

- Philippe of France (1730–1733), Duke of Anjou

- Princess Marie Adélaïde of France (1732–1800), daughter of Louis XV

- Princess Victoire of France (1733–1799), daughter of Louis XV

- Princess Sophie of France (1734–1782), daughter of Louis XV

- Princess Louise of France (1737–1787), daughter of Louis XV,

- Louis Joseph, Dauphin of France (1781–1789), first son of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

- Princess Sophie Hélène Béatrice of France (1786–1787), second daughter of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette

- Henri de La Tour d'Auvergne, Vicomte de Turenne (1611–1675), Maréchal General de France.

Timeline

[edit]- c. 250 AD – Martyrdom of Saint Denis

- After 313 – Construction of first basilica

- 451–459 – Basilica enlarged by Saint Genevieve

- 626–639 – Further enlargement by Dagobert, first King to have sepulchre in the church

- 775 – New church dedicated in presence of Charlemagne

- 1122–1151 – Suger is Abbot of Saint-Denis

- 1140–1144 – Reconstruction of the chevet with Gothic features

- 1231 – Reconstruction of the upper chevet and the nave

- 1267 – Louis IX inaugurates the royal necropolis

- c. 1320–1324 – Construction of six chapels along the north side of nave

- 1364 – Charles V of France commissions his tomb in the church

- 1572 – Beginning of the construction of the mausoleum of the Valois dynasty

- 1771 – Removal of the statue-columns installed by Suger on the west front

- 1792 – Final office celebrated by the monks, following the French Revolution

- 1805 – Beginning of restoration ordered by Napoleon

- 1813 – New restoration begun by architect François Debret

- 1845 – Collapse of Debret's rebuilt north spire. Eugène Viollet-le-Duc becomes chief architect of restoration.

- 1862 – The basilica is classified a French historical monument

- 1966 – The basilica becomes the cathedral of the new department of Seine-Saint-Denis.

- 2004 – The heart of Louis XVII is transferred to the chapel of the Bourbons.[69]

Gallery

[edit]-

The choir at sunset

-

The clerestory windows

-

Depiction of the Trinity over the main entrance

Abbots

[edit]See also

[edit]- Early Gothic architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- Cathedral diagram

- Martyrium of Saint Denis, Montmartre

- List of Gothic cathedrals in Europe

- French Gothic stained glass windows

- List of tourist attractions in Paris

References and sources

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

References

[edit]- ^ Site of the Basilique-cathédrale de Saint-Denis, retrieved 23 November 2020

- ^ Enclopaedia Britannica online, "Gothic Architecture", retrieved 23 November 2020

- ^ Watkin 1986, pp. 126–128.

- ^ a b Lours 2018, p. 346.

- ^ A grave from the exterior necropolis

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia: Abbey of Saint-Denis

- ^ Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method.

- ^ Basilicas of France.

- ^ "Signature de la convention-cadre pour la reconstruction de la flèche et de la tour nord de la basilique de Saint-Denis". www.culture.gouv.fr (in French). Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ CMN. "Reconstruction de la tour et de la flèche nord de la basilique cathédrale Saint-Denis - CMN". www.saint-denis-basilique.fr (in French). Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Le Deley, Jade (17 May 2024). "A la basilique de Saint-Denis, un chantier au sommet". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved 15 December 2024.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 2.

- ^ Doublet, Dom (1625). Histoire de l'abbaye de Saint-Denys en France. pp. 164–165.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Vita S. Eligius, edited by Levison, on-line at Medieval Sourcebook

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 3.

- ^ DeSmet, W.M.A. (1981). Mammals in the Seas: General papers and large cetaceans. Whaling During the Middle Ages. Food & Agriculture Org. ISBN 978-9251005132.

- ^ Lindy Grant, Abbot Suger of St.Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth century France, Longman, 1998

- ^ Sumner McKnight Crosby, The Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis from Its Beginnings to the Death of Suger, 475–1151, Yale University Press, 1987

- ^ a b c d Plagnieux 1998, p. 4.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Watkin 1986, p. 127.

- ^ O'Hanlon 1873, p. 241.

- ^ Watkin 1986, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Bruce Watson, Light: A Radiant History from Creation to the Quantum Age. Bloomsbury, 2016, p 52.

- ^ Lindy Grant, Abbot Suger of St. Denis: Church and State in Early Twelfth Century France, Addison Wesley Longman Limited, 1998

- ^ Stephen Gardner, "Two Campaigns in Suger's Western Block at Saint-Denis", Art Bulletin, Vol.44, part 4, 1984, pp. 574–87

- ^ a b Plagnieux 1998, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 10.

- ^ H. Honour and J. Fleming, The Visual Arts: A History. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005. ISBN 0131935070

- ^ "L'art Gothique", section: "L'architecture Gothique en Angleterre" by Ute Engel: L'Angleterre fut l'une des premieres régions à adopter, dans la deuxième moitié du XIIeme siècle, la nouvelle architecture gothique née en France. Les relations historiques entre les deux pays jouèrent un rôle prépondérant: en 1154, Henri II (1154–1189), de la dynastie Française des Plantagenêt, accéda au thrône d'Angleterre." (England was one of the first regions to adopt, during the first half of the 12th century, the new Gothic architecture born in France. Historic relationships between the two countries played a determining role: in 1154, Henry II (1154–1189), of the French Plantagenet dynasty, ascended to the throne of England).

- ^ John Harvey, The Gothic World

- ^ Georgia Sommers Wright, "A Royal Tomb Program in the Reign of St Louis", in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 56, No. 2 (Jun 1974) pp. 224–243

- ^ Christopher Wilson, The Gothic Cathedral: The Architecture of the Great Church 1130–1530, Thames & Hudson, 1992

- ^ Caroline Bruzelius, The Thirteenth century Church at St-Denis, New Haven, 1985

- ^ Images of Medieval Art and Architecture – Félibien, archived on 2 December 2009.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f Plagnieux 1998, p. 18.

- ^ a b c Plagnieux 1998, p. 32.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 22.

- ^ "L'affaire de la tour nord : La querelle des anciens et des modernes". Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis (in French). Seine-Saint-Denis Tourisme. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Bourdon, Gwenaël (30 January 2017). "Basilique Saint-Denis : le chantier de la flèche freiné dans son élan". Le Parisien (in French). Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "Saint Denis Cathedral spire". Paris Digest. 2019. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "Accord définitif de l'Etat : la flèche de la Basilique sera remontée". Basilique Cathédrale de Saint-Denis (in French). Seine-Saint-Denis Tourisme. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ Sage, Adam (16 November 2021). "French academics at odds over €25m plans to rebuild spire of Basilica of Saint-Denis". The Times.

- ^ Morin, Hervé (9 April 2023). "Basilica of Saint-Denis: Newly discovered graves bring back the past". Le Monde.

- ^ "Light returns to the stained glass of the Saint-Denis Basilica". France 24. 3 February 2023.

- ^ a b c Plagnieux 1998, p. 16.

- ^ William Chester Jordan, A Tale of Two Monasteries: Westminster and Saint-Denis in the thirteenth century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009) Chapters 2–7.

- ^ Stanley, David J. (2006). "The Original Buttressing of Abbot Suger's Chevet at the Abbey of Saint-Denis". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 65 (3): 334–355. doi:10.2307/25068292. ISSN 0037-9808. JSTOR 25068292.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Plagnieux 1998, p. 8.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, pp. 11–15.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 12.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 24.

- ^ a b Plagnieux 1998, p. 46.

- ^ a b Lindsay, Suzanne Glover (18 October 2014). "The Revolutionary Exhumations at St-Denis, 1793". Center for the Study of Material & Visual Cultures of Religion. Yale University.

- ^ a b Plagnieux 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Broughton, Philip Delves (7 June 2004). "Tragic French boy king's heart finds a final resting place after 209 years". Daily Telegraph. London, UK. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ a b Plagnieux 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Plagnieux 1998, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Martindale 1967, p. 42.

- ^ Pamela Blum, Early Gothic Saint-Denis: Restorations and Survivals, Berkeley, 1992

- ^ a b Base Palissy: PM93000477, Ministère français de la Culture. (in French)

- ^ Knecht, 227. Henry's gesture is now unclear, since a missal, resting on a prie-dieu (prayer desk), was removed from the sculpture during the French revolution and melted down.

- ^ Timeline events from Plagnieux, Philippe, "La basilique cathédrale de Saint-Denis",(1998), p. 49

- ^ "Birth of the Gothic: Abbot Suger and the Ambulatory at St. Denis". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

Sources

[edit]- Félibien, Michel. 1973. Histoire de l'abbaye royale de Saint-Denys en France: Lettre-préf. de M. le Duc de Bauffremont. Introd. de Hervé Pinoteau. 1. [Nachdr. d. Ausg. Paris, 1706]. – 1973. – 524 S. Paris: Éd. du Palais Royal.

- O'Hanlon, John (1873), Lives of the Irish saints, retrieved 2 August 2021

- Saint-Denis Cathedral, Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, Editions Ouest-France, Rennes

Bibliography

[edit]- Gerson, Paula Lieber. (1986). Abbot Suger and Saint-Denis: a symposium, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0870994081

- Martindale, Andrew (1967). Gothic Art. Thames and Hudson (in English and French). ISBN 2878110587.

- Conrad Rudolph, Artistic Change at St-Denis: Abbot Suger's Program and the Early Twelfth Century Controversy over Art (1990)

- Conrad Rudolph, "Inventing the Gothic Portal: Suger, Hugh of Saint Victor, and the Construction of a New Public Art at Saint-Denis," Art History 33 (2010) 568–595

- Lours, Mathieu (2018). Dictionnaire des Cathédrales. Éditions Jean-Paul Gesserot. ISBN 978-2755807653.

- Plagnieux, Philippe (1998). La basilique cathédrale de Saint-Denis. Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN 978-2757702246.

- Conrad Rudolph, "Inventing the Exegetical Stained-Glass Window: Suger, Hugh, and a New Elite Art," Art Bulletin 93 (2011) 399–422

- Watkin, David (1986). A History of Western Architecture. Barrie and Jenkins. ISBN 0712612793.

- Watson, Bruce, Light: A Radiant History from Creation to the Quantum Age, (London and NY: Bloomsbury, 2016).

External links

[edit]- Website for Basilica of Saint-Denis, Centre des monuments nationaux

- Map of the tombs in Saint-Denis Basilica

- The Treasures of Saint-Denis – scholarly article from 1915 on the important and mostly destroyed treasures

- L'Internaute Magazine: Diaporama (in French)

- Satellite image from Google Maps

- Saint-Denis, a town in the Middle Ages

- Photos of tombs and the Basilica (in French)

- Photos of the windows at the Basilica

- history and pictures of the Basilica (in French)

- The Sumner McKnight Crosby Papers from The Cloisters Library, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Buildings and structures completed in 1144

- 12th-century Roman Catholic church buildings in France

- Churches in Seine-Saint-Denis

- Roman Catholic cathedrals in France

- Benedictine monasteries in France

- Basilica churches in France

- Monuments historiques of Seine-Saint-Denis

- Gothic architecture in Paris

- Burial sites of the House of Évreux

- Burial sites of the House of Albret

- Burial sites of the House of Champagne

- Burial sites of the House of Valois-Anjou

- Burial sites of the House of Valois-Angoulême

- Burial sites of the House of Valois-Orléans

- Burial sites of the House of Valois

- Saint-Denis, Seine-Saint-Denis

- Monuments of the Centre des monuments nationaux

- Burial sites of the House of Bourbon (France)

- Burial sites of the Merovingian dynasty